|

Lenten Bible Blog, 6th Sunday of Lent (Palm Sunday) (Psalm 118:1-2, 19-29; Mark 11:1-11 or John 12:12-16)  Palm Sunday Procession, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=54312. Original source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/johndonaghy/3415402416/. Palm Sunday Procession, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=54312. Original source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/johndonaghy/3415402416/. Ps 118 stems from someone worshiping at the temple. The white spaces between many verses (e.g., between vv. 20 and 21 or between vv. 25 and 26) indicate that one or another element of the liturgy has been preserved in this psalm. For example, vv. 1-4 provide both liturgical instructions and a refrain. And there are references to movement into the temple, vv. 19-20 and 26-27. The Hebrew word in 118:1, which is translated as “steadfast love,” can also be translated “covenant loyalty,” (e.g., Deut 7:9). Read this way, the psalm participates in Israel’s covenantal traditions, which have been a hallmark in lections during this Lenten season. Christians have understood the psalm in creative ways. They construe “This is the day that the Lord has made” (v. 24) as a reference to Sunday, and even more to Easter. They view “the stone that the builders have rejected” (v. 22) as a reference to Jesus’ rejection (Mk 12:10). They claim that the statement “This is the Lord’s doing” (v, 23) refers to Jesus’ passion (Mk 12:11). A prayer for help, “Save us!” (v. 25), appears as “Hosanna!” in Mk 11:9. “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (v. 26) is cited in Mk 11:9 as a reference to Jesus. In sum, Psalm 118 became an important way for expressing early Christian understandings of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. The alternate NT lections offer Marcan and Johannine accounts of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. They pick up on the idea of “a festal procession with branches” in our Psalm (v. 27). And they build on Old Testament royal traditions. Noteworthy is Jesus riding on a colt, which likely refers to a procession in which a king rides on “a colt, the foal of a donkey” (Zech 9:9). This king is both “triumphant and victorious” and “humble,” qualities that early Christians attributed to Jesus. The procession also included spreading cloaks on the ground before a king, a practice attested in 2 Kgs 13. And the presence of leafy branches as a part of a victorious procession is present in 1 Macc 13:51. Moreover, the specific reference to palm branches, present only in John 12:13, is also part of such processions, so 2 Macc 10:7. These royal allusions were made specific when the crowd that gathered around Jesus spoke about “the coming kingdom of our ancestor David” (Mk 11:10) and said about him, “the King of Israel” (John 12:13). It is no wonder that the Romans viewed this procession as an act of sedition. Strikingly, “the disciples did not understand these things.” (John 12:16). The crowd clearly thought that Jesus was the anticipated king, whereas the disciples did not yet know the full significance of what was about to happen.

0 Comments

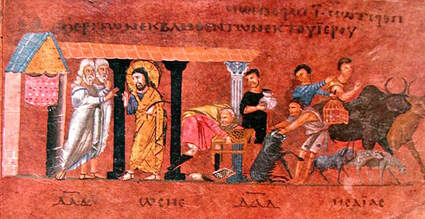

Lenten Bible Blog, 5th Sunday of Lent (Jer 31:31-34; Psalm 51:1-12 or 119:9-16; Heb 5:5-10; John 12:20-33)  Meu Coracao/My Heart, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=54138. Original source: Amanda Vivan, Flickr Creative Commons. Meu Coracao/My Heart, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=54138. Original source: Amanda Vivan, Flickr Creative Commons. The reading from Jeremiah includes yet another element in the covenant tradition: a new covenant (following the covenants involving Noah, Abraham, and, especially, the one made at Sinai). Instead of a covenant inscribed on stone tablets, it will be written on people’s hearts. What this means in concrete terms is less clear. On the one hand, humans will not need to teach each other what the torah means; they will “know me,” says the Lord. On the other hand, God will forgive their sin//iniquity, which suggests that even under this new covenant life will not be perfect. (For resonances of this text in early Christianity, see Lk 22:20; 2 Cor 3:6.) Though Ps. 51 does not refer overtly to a covenant, it reflects the concerns of an individual who is deeply aware of his sins, acts violating ethical and religious norms of the Sinai covenant. The poet asks for forgiveness—and more: a clean heart//a new spirit. This request testifies to the difficulty the psalmist has experienced in living up to the expectations of the covenant. In contrast, the author of Ps. 119 holds out hope that she can hold God’s word in her heart and live in an appropriate way. These psalms reflect two different moods that the religious person can have--at one time, despondence over shortcomings and, at another time, optimism about living an ethical life. Hebrew 5:5-10 reflects on Jesus as one who, through his life and death, was “made perfect.” As such, he can fulfill the role of the high priest in a new way. The high priest had been responsible for offering sacrifices for both himself and others (Lev 7:27). Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross was “a single sacrifice for sins” (Heb 10:12). His sacrifice offers members of the Christian community the opportunity to share in that perfection (Heb 10:14). The author of Hebrews therefore claims that Jesus in the role of high priest, is “the mediator of a new covenant” (Heb 9:15). Action in this Johannine scene is initiated by “some Greeks,” foreigners who had come to Jerusalem for Passover. Not only do they want to worship; they want to “see Jesus,” who, when he hears about their request, reflects about his death (v. 24), those who lose or keep their lives (v. 25), and the way of servanthood (v. 26). We do not know if the Greeks actually saw Jesus, but his three sayings offer a response to their quest. In the agricultural metaphor, they learn that Jesus death will lead to the fertility represented in the growth of the Christian community. In the second saying, they are told about the way to eternal life. And in the final statement, Jesus uses the language of movement—“following”—and place—“there”—to identify features of the servant life that will lead to being honored by God. Such is life in the new covenant.  Interior of the Church of the Light, designed by Tadao Ando, in Ibaraki, Osaka Prefecture. The original uploader was Bujatt at English Wikipedia. - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Arch2all using CommonsHelper., CC BY-SA 2.5. Interior of the Church of the Light, designed by Tadao Ando, in Ibaraki, Osaka Prefecture. The original uploader was Bujatt at English Wikipedia. - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Arch2all using CommonsHelper., CC BY-SA 2.5. After the Israelites left Egypt, but before they entered the land of Canaan, they lived in the wilderness. It was a time fraught with difficulty. Throughout the books of Exodus and Numbers, the complained bitterly about their harsh existence. These complaints begin as early as Exodus 14:10-12 and continue up through this lection, in which they criticize not only Moses but also God. After the deity punishes them, he tells Moses to make a sculpted snake and to lift it up on a pole so that the people could see it and live, a kind of sympathetic magic. The verses in Psalm 107 are the sort of song that those in Num. 21 might have sung after they have been “saved from their distress.” The psalm makes clear that God intervened because the people “cried to the Lord in their trouble.” The aforementioned stories in Exodus and Numbers often begin with the people complaining to Moses, but only later in the stories do they offer a lament about their plight and ask God for help. The distinction is important. The Psalter is filled with laments—the most frequent kind of Psalm--but not with complaints. The apostle Paul reflects on a living death, “following the course of the world,” and avows that Christians have been “made alive” through the death and resurrection of Jesus. Here, as was the case with the OT lections, God is one who provides life for those who have experienced death. God does this “out of the great love with which he loved us,” a motif that occurs in the Johannine text. The lection in John refers explicitly to the scene in Numbers and views it as a foreshadowing of Jesus lifted up on a cross, one who can provide life to those who see and understand the importance of his death and resurrection. This reading from John also includes a verse (v. 16) that we sometimes see on placards at sporting events. Such usage presumes that it is a stand-alone text, and the fact that it is printed as a separate paragraph lends some credence to this approach. It’s most fundamental theological claim is this: God loved the world. Even the famous prologue to this gospel, does not make this claim. The lection uses several verbs to denote God’s concrete action: God gave his only son; God sent his son. And this verse offers the reason for such action: it is rooted in God’s providential love for all that has been created, including all people. The gospel writer uses the diction of ‘God giving’ on multiple occasions. It implies that God’s Son is a gift to the world. Not all gifts are accepted. John challenges his readers to accept or believe in this gift, which involves the granting of “eternal life.”  Cleansing of the Temple, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56497 [retrieved March 2, 2021]. Original source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. /wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. Cleansing of the Temple, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56497 [retrieved March 2, 2021]. Original source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. /wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. The Ten “Words” (Exod 43:28; Deut 4:13; 10:4)) are often known as the Ten Commandments. (Religious traditions enumerate them differently.) The Words have a complicated early history: they are given (20:1), written (24:4), recited (24:7), shattered (32:19), and rewritten (34:27-28). The Ten Words are constitutive of the covenant between God and the people. (This third or Sinai covenant follows the earlier covenants between God and Noah and between God and Abraham.) There are two versions of the Ten Words: Exod 20:1-17 and Deut 5:6-21. These Ten covenantal Words involve two fundamental relationships: between God and humanity--the initial four “words”—and between humans--the final six “words.” These words are not exhaustive; they reflect essential religious and ethical norms. They serve as the basis for the people of God’s communal life. When the Psalmist declares, “The heavens are telling the glory of God,” but then says, “Their voice is not heard,” one wonders what sort of “telling” is taking place, especially since ‘their words go to the end of the world.” This mystery is compounded when the poet refers to her own words, “let the words of my mouth be acceptable.” The words attested in this psalm are both pervasive and quiet. The first two lections explore significant words: God’s words, the heavens’ words, and human words. In this regard, it is important to recognize that virtually all of the words in the Psalms are human words, not God’s, and yet they have become the Word of God. Paul, too, reflects about words, foolish and wise ones. But there is a problem; God’s wisdom, “Christ crucified,” is a stumbling block (literally, a scandal) for Jews and foolishness for Gentiles. Nonetheless, Paul maintains that Christ is the (true) wisdom and the power of God. Wise words are, in Paul’s view, unconventional words that challenge prior conceptions of what is true. The scene of the temple’s cleansing includes a shift in the meaning of words: “in the temple” and “my Father’s house” to the “the temple of his body.” The first two phrases clearly refer to an architectural structure, the Second Temple. Verses 14-16, a long sentence in Greek, underscore Jesus’ intense and focused movement through the physical temple. When asked about the significance of what he was doing, Jesus speaks of destroying the temple and rebuilding it in three days, a clear allusion to his death and resurrection. That is why the gospel writer weighs in and says directly to the reader: “He was speaking about the temple of his body.” As Gail O’Day (NIB IX, 544) has shown, the Gospel of John claims that the locus of God’s activity has changed: from the physical temple to the body and person of Jesus Christ. John is less interested in thinking about reforms at the temple than he is in claiming that Jesus has become more important than the temple. |

Details

AuthorDavid Petersen is Franklin N. Parker Professor Emeritus of Old Testament, Emory University. While at Emory, he was also Academic Dean at the Candler School of Theology, where he received the Emory Williams Distinguished Teaching Award. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed