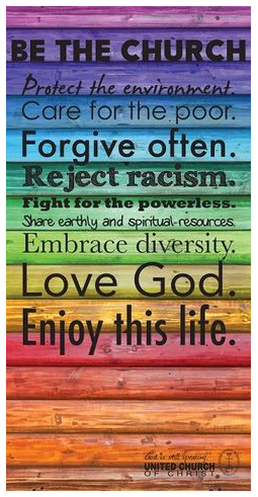

uccresources.com/collections/be-the-church uccresources.com/collections/be-the-church When people come into a progressive church setting one of the most liberating and, for some, unsettling things is the lack of a set creed. Many churches and denominations put their beliefs, often in the form of a creed, right up front. They continue a long tradition within Christianity of identifying “the faith” with “a certain set of orthodox beliefs.” Since the Reformation, we are used to the idea that one group’s “orthodox beliefs” might differ significantly from anther group’s “orthodox beliefs,” but in general the idea that a church is defined by its beliefs has reigned unchallenged. Matters of governance, ethics, relationship with the broader society, liturgy, hymnody and discipline all have generally been regarded as secondary to beliefs. Some people find the lack of a creed as highly freeing, since they are now free (and responsible) to think for themselves. They are liberated from authority figures determining the bounds of their thinking, and can pursue the things they have wondered about. Sometimes they find resolutions, other times one question leads into yet another and another. At times, they then want some guidance to navigate the wide-open spaces, and here is where the challenge begins. The response to “So, what do you believe?” is often quite awkward, because “belief” is not the chief marker or binder of our life together. We generally regard statements like creeds to be “testimonies of faith” rather than “tests of faith.” That is, they are benchmarks showing us what the best thinking and faith work of our ancestors accomplished for their time and place, but are not something we are required to conform to in our time and place. Creeds can be good to know about, since they show what questions vexed our forbears, can alert us to potential dead ends, and provide us helpful tools and categories for our own inquiry. We are often clearer about what we do not believe than what we do believe. So progressives generally disbelieve in “miracles,” which puts traditional doctrines like the Exodus, Virgin Birth or Resurrection into a bin marked “rethink, retool or reject.” We often do not believe in an interventionist God, who “suspends the laws of nature” at times, which puts traditional understandings of prayer into question; we find answers to prayer not in radical results but in renewed relationship with God. We are suspicious of claims of special revelation, whether for the inspiration of the Bible or the authority of church leaders, which raises keen questions of how we discern and value religious authority in self and others. Moreover, the whole discussion of belief in this or that doctrine seems quite beside the point: We are constituted as a community not by believing together but by working together. We have found that we can work to end homelessness without agreeing on whether Jesus turned water into wine or Welch's. We can work to prevent war, and end the ones we are engaged with, without agreeing whether to immerse adults or sprinkle babies for baptism. We can open our doors to the immigrant, stranger and alien “because you were once slaves in Egypt” (Leviticus 19:24, etc.), regardless of whether we regard the sojourn in Egypt and Exodus as historical or metaphorical (or whether we are of Israelite descent). Many times the question is not so much “What do you believe?” as “How do you believe?” What is the motivation for your beliefs? Do you believe this or that doctrine so you can be “right” and someone else “wrong”? Even “liberals” can have “fundamentalist” spirits. Do you believe something so you can draw a bright line between you and the non-believer? And then assume that God will bless you and curse them? But then, “What about the people who I love who are on the wrong side of the church’s bright line?” This is the root cause of so many people who sadly walk away from the church, for they cannot believe that God’s love is so narrow that God refuses to love someone that they are quite able to love. If you scratch at the surface of our working together, you will likely find some common beliefs we do share. We welcome all people because we see no exceptions in “God so loved the world, that God gave the only Son so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life” (John 3:16). We value our fellow human because we are all made in the image and likeness of God and therefore have value like God’s (Gen. 1:26, 9:6, etc.) We are trying to figure out in practical ways what it means to “love God… and our neighbor as our selves” (Mark 12:30, Romans 13:9, etc.). We share responsibility for the ecological health of our planet, to manage it wisely for future generations (Gen. 1:28, Psalm 24:1, etc.). We try to emulate Christ, not as king and ruler, but as servant (Philippians 2:5ff, John 13:1-17). In all these cases, we are working our way into belief, not believing our way into behaving. Just as if you want to feel in love with your beloved, you don’t introspect and try to drum up certain feelings, you do good and kind and thoughtful things for them, and the feelings follow. At core, love is a verb rather than an affection; so is faith. So maybe the question is not “What do you believe?” or even “How do you believe?” but “What do you love?” If we drill down to Jesus’ Great Commandment, that gives us two great objects: God and Neighbor. There will be lots of room for different beliefs about who God is and how we know God, and there may be a lot of different actions to love our Neighbor.* But by focusing on our common work together, we can create the sort of community where there is space to discuss how God has drawn us together for such action. What would the church be like if its theology had been created not in the classroom over the philosophy textbook but in the company break room, the factory union hall, the immigrant’s detention center, or the homeless encampment? Peace, Rev. Dr. Mark Lee *Not every answer to these questions will be right: there are ways to go clear off the rails. Recall that the Inquisition claimed it was loving the neighbor by torturing them to get right with G*d as the Inquisitors understood him. But how to discern what is true of God and loving towards neighbor is a discussion for another day. AuthorThe Rev. Dr. Mark Lee brings a passion for Christian education that bears fruit in social justice. He has had a lifelong fascination with theology, with a particular emphasis on how Biblical hermeneutics shape personal and political action. Read more about Mark. |

Details

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed