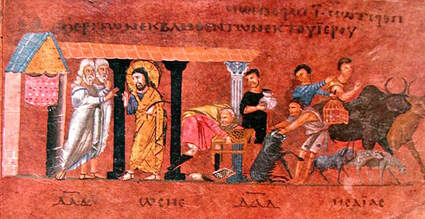

Cleansing of the Temple, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56497 [retrieved March 2, 2021]. Original source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. /wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. Cleansing of the Temple, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56497 [retrieved March 2, 2021]. Original source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. /wiki/File:Rossano_Gospels_-_Cleansing_of_the_Temple.jpg. The Ten “Words” (Exod 43:28; Deut 4:13; 10:4)) are often known as the Ten Commandments. (Religious traditions enumerate them differently.) The Words have a complicated early history: they are given (20:1), written (24:4), recited (24:7), shattered (32:19), and rewritten (34:27-28). The Ten Words are constitutive of the covenant between God and the people. (This third or Sinai covenant follows the earlier covenants between God and Noah and between God and Abraham.) There are two versions of the Ten Words: Exod 20:1-17 and Deut 5:6-21. These Ten covenantal Words involve two fundamental relationships: between God and humanity--the initial four “words”—and between humans--the final six “words.” These words are not exhaustive; they reflect essential religious and ethical norms. They serve as the basis for the people of God’s communal life. When the Psalmist declares, “The heavens are telling the glory of God,” but then says, “Their voice is not heard,” one wonders what sort of “telling” is taking place, especially since ‘their words go to the end of the world.” This mystery is compounded when the poet refers to her own words, “let the words of my mouth be acceptable.” The words attested in this psalm are both pervasive and quiet. The first two lections explore significant words: God’s words, the heavens’ words, and human words. In this regard, it is important to recognize that virtually all of the words in the Psalms are human words, not God’s, and yet they have become the Word of God. Paul, too, reflects about words, foolish and wise ones. But there is a problem; God’s wisdom, “Christ crucified,” is a stumbling block (literally, a scandal) for Jews and foolishness for Gentiles. Nonetheless, Paul maintains that Christ is the (true) wisdom and the power of God. Wise words are, in Paul’s view, unconventional words that challenge prior conceptions of what is true. The scene of the temple’s cleansing includes a shift in the meaning of words: “in the temple” and “my Father’s house” to the “the temple of his body.” The first two phrases clearly refer to an architectural structure, the Second Temple. Verses 14-16, a long sentence in Greek, underscore Jesus’ intense and focused movement through the physical temple. When asked about the significance of what he was doing, Jesus speaks of destroying the temple and rebuilding it in three days, a clear allusion to his death and resurrection. That is why the gospel writer weighs in and says directly to the reader: “He was speaking about the temple of his body.” As Gail O’Day (NIB IX, 544) has shown, the Gospel of John claims that the locus of God’s activity has changed: from the physical temple to the body and person of Jesus Christ. John is less interested in thinking about reforms at the temple than he is in claiming that Jesus has become more important than the temple. Comments are closed.

|

Details

AuthorDavid Petersen is Franklin N. Parker Professor Emeritus of Old Testament, Emory University. While at Emory, he was also Academic Dean at the Candler School of Theology, where he received the Emory Williams Distinguished Teaching Award. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed