|

Isaiah 64.1-9(10-12) * [text at bottom of post]

First Sunday in Advent Plymouth Congregational Church, UCC The Rev. Jane Anne Ferguson Twentieth century poet, Langston Hughes, wrote his poem, "Dreams" [1], in 1922. It was one of his earliest works and one of his best remembered.

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die Life is a broken-winged bird That cannot fly. Hold fast to dreams For when dreams go Life is a barren field Frozen with snow.

Hughes’ images are incredibly poignant for us as we enter Advent in this pandemic ridden, politically and racially divisive year. How do we hold on to our national dreams of health and peace and cooperation and justice and abundance and equality for all this Advent? Our faith dreams of building God’s realm here and now on earth? How do we dream Hope? The ancient people of God, the Israelites of the 6th century B.C.E., were wondering the same thing when they heard the prophet cry out to God in lament, “O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence…” They, too, were wondering if they could dream hope and they were trying hard to hold on the “awesome deeds” of God they had experienced with surprise and joy in the past. Why was God not acting like God way back in the day when they were delivered from slavery in Egypt? Or even not so far back in the day when they were led out of exile in Babylon and back to Jerusalem to rebuild their lives in the promised land and to rebuild the temple of the Most High? Instead of flowing springs in the desert and straight highways of policy following God’s law, instead of an oasis of plenty, they had returned from exile ready to rebuild only to find strife and hardship. There were polemical factions among the differing tribes; they were short on cooperation. Physically rebuilding the temple along with new infrastructures for simply living together was much more difficult than they had ever imagined. They felt abandoned by the God whom the prophet had promised would restore their fortunes and renew their abundance. Perhaps, they didn’t have a pandemic, but they knew well the unrest of extreme civil discord at a time they needed to work together to survive. The book of Isaiah spans three centuries of the Israelites’ relationship with God. The original 8th century prophet, Isaiah, prophesied to the rulers and people of Judah when the Babylonian empire was encroaching upon them, eventually conquering Jerusalem. Much of the population was captured and taken into exile in Babylon where they learned to make their lives and honor their God in a foreign land. In the late 7th and into the 6th century B.C.E., a new prophet arose in the midst of exile writing in the name and fashion of Isaiah. These first two prophets gave the people the wondrous and inspiring poetry and prose of hope that we often hear this time of year: “the people who walk in darkness have seen a great light,” “you shall go out with joy and be led forth in peace, the trees shall clap their hands,” “the lion shall lie down with the lamb…and a little child shall lead them.” Now we hear from the prophet who is with the people after the return from exile…. things are looking very bleak….and the prophet speaking in the tradition of Isaiah loudly laments…”Where are you, God? Come down to us! You forgot us and so now we have sinned…. we are fractured as a people, hanging on by a thread… you have hidden from us and so even our best efforts are like filthy rags…we are undone!” How many times in this past year could any of us, each of us, have lifted up the sentiments of this lament to God? For goodness sake – literally ¬– Where are you, God?!? For God’s sake – literally – show yourself! Fix us, deliver us, restore us to your presence. As the poet warned us early in this sermon, without our dreams, without hope, life is like a broken-winged bird, crippled and dying. Life is barren, about to be snuffed out in the frozen depths of our deep disconnection with you, Holy One. The ancient prophet’s cry in this 64th chapter of Isaiah moves us from anger and despair, which we know all too well in our times, to broken-hearted sobbing sorrow and lament which we also know in these times of pandemic and racial violence. If it feels excruciating and you are wondering what kind of introduction to Advent is this? – you are getting it. You see, it turns out that authentic lament with all its anger and confession and sorrow is psychologically good for us and good for our souls. Bottling up all our feelings in stoic silence does not solve any issue. It alienates us from others and its bad for our blood pressure. The structure of lament is an appropriate practice for expression. Spiritually, lament breaks open our hearts before God. And when our hearts are broken as they have been in this year, broken open, our eyes and our ears can open as well. It turns out that the prophet does not leave us despairing in the dirt, fading away like dead leaves, but in acknowledging our brokenness before God, the prophet points us paradoxically to God who is with us in our vulnerability and pain. “8 Yet, O LORD, you are our Father [our Maker]; we are the clay, and you are our potter; we are all the work of your hand. 9 Do not be exceedingly angry, O LORD, and do not remember iniquity forever. Now consider, we are all your people.” The ancient stories of God’s past deliverance of God’s people proclaimed by prophets are not sentimental, smothering nostalgia nor are they a delusional panacea denying the pain of the present. They are beacons of light drawn from the collective memories of God’s people as a source of hope. God’s prophets are not fortune-telling predictors of the future events. They are witnesses to God’s presence in the world and in our lives, God, who is vulnerable and nurturing and suffering with us. God who tends and shapes God’s people – ALL of God’s people, not just a special set of followers of particular religious tenants – all of the people, all of humanity, all of creation, intimately shaped in love by God’s creating Spirit, as a potter shapes clay to make useful vessels. The prophet knew that when God seems hidden, people are lonely and hurting. And this is when we act out in fear, sinning against one another. The prophet also knew that God is always hiding in plain sight in the pain of our very lives and situations. God is not a coy, disguised superhero… Clark Kent, the humble bumbling reporter, one minute and Superman saving the world the next minute. The character of God is “divine determination relating to the world “through the vulnerable path of noncoercive love and suffering service rather than domination and force.” [2] This determined loving, suffering character of God is why we can dream hope even in the worst of times. We have Love Divine with us, within us, among us, binding us together even in conflict and seeming de-construction of all that we hold dear. This is the God of the Advent call, “O come, O come, Emmanuel – God with us!”

Perhaps you saw the artwork for this week from our Advent devotional booklet in the Plymouth Thursday Overview and Saturday Evening emails. Its titled, “Tear Open the Heavens” and painted by Rev. Lauren Wright Pittman, a founding partner of Sanctified Art, the group who wrote our devotional. Look at it with me for just a moment…. What do you see? I see weeping….spilling over love, an overflowing pottery pitcher, mountains, trees, wise eyes, divine presence, the colors of love, the actions of love.

We can dream hope because God is dreaming with us as we weep and laugh and work together with God. As we sometimes rage against the pain and darkness – with God. As we sometimes hide from one another and from God. Yet God, Divine Love, is always dreaming hope and dreaming love through us, through our lives. Therefore, we can hold fast to our dreams because God is holding fast to us even when we are not watching. “O that you would tear open the heavens and come down,” we say. And God says, “I have. I am with you. I never left.” Amen.

Pastoral Prayer

Holy One, we come before you this morning with hopes for dreaming hope, for building hope, for being hope in our corners of your world. We long to get our hands dirty with the work of hope as we raise money for homelessness prevention, as we support the immigrants in our community, as we learn together with our children and youth about the active hope of Advent, as we support one another in these difficult times – even if distanced. As our thoughts and preparations turn toward the Christmas season, keep us ever-mindful of gratitude for our blessings, ever-giving from those same gifts for you have given them to us for sharing. Bless all those who struggle with illness of any kind, those who wait for much needed surgery or procedures because the hospitals are full of Covid 19 patients who need the frontline care. Bless the caregivers of all kinds, whether in a facility or at home. Bless the children and youth and young adults as they go back to remote school. Bless those who mourn the loss of a loved one. Bless our country in this time of transition. May we all turn toward much needed healing of racial and political divides. Bless us all as we seek to participate in your hope for your creation. Hear us now as we say the prayer Jesus taught us to say, “Our Father, who art….

[1] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/150995/dreams-5d767850da976

[2] Scott Bader-Saye, “Theological Perspective”, Isaiah 64.1-9, First Sunday in Advent, Year B, Feasting on the Word, Year B, Volume 1, David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, eds. (Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville, KY, 2008, 6.)

©The Reverend Jane Anne Ferguson, 2020 and beyond. May only be reprinted with permission.

* Isaiah 64.1-9[10-12]

1 O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence — 2 as when fire kindles brushwood and the fire causes water to boil — to make your name known to your adversaries, so that the nations might tremble at your presence! 3 When you did awesome deeds that we did not expect, you came down, the mountains quaked at your presence. 4From ages past no one has heard, no ear has perceived, no eye has seen any God besides you, who works for those who wait for him. 5You meet those who gladly do right, those who remember you in your ways. But you were angry, and we sinned; because you hid yourself, we transgressed. 6We have all become like one who is unclean, and all our righteous deeds are like a filthy cloth. We all fade like a leaf, and our iniquities, like the wind, take us away. 7 There is no one who calls on your name or attempts to take hold of you; for you have hidden your face from us and have delivered us into the hand of our iniquity. 8 Yet, O LORD, you are our Father; we are the clay, and you are our potter; we are all the work of your hand. 9 Do not be exceedingly angry, O LORD, and do not remember iniquity forever. Now consider, we are all your people. (10 Your holy cities have become a wilderness, Zion has become a wilderness, Jerusalem a desolation. 11 Our holy and beautiful house, where our ancestors praised you, has been burned by fire, and all our pleasant places have become ruins. 12 After all this, will you restrain yourself, O LORD? Will you keep silent, and punish us so severely?) AuthorAssociate Minister Jane Anne Ferguson is a writer, storyteller, and contributor to Feasting on the Word, a popular biblical commentary. Learn more about Jane Anne here.

0 Comments

Genesis 12.1 - 6 & Matthew 5.13 – 16

The Rev. Hal Chorpenning, Plymouth Congregational UCC Fort Collins, Colorado

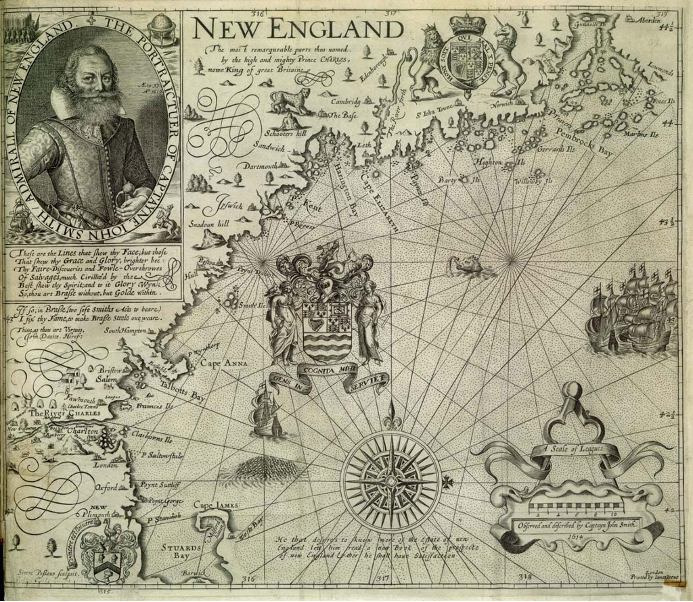

When American historians look back at the year 2020, they will certainly remember the coronavirus and the presidential election. Yet back in January, I thought they’d be remembering something else. November 11th marked the 400th anniversary of the landing of the Separatist Pilgrims in New England after a sea voyage of 66 days. They had intended to land near the Hudson River, but rough seas forced them to the relative safety of Cape Cod Bay, and on December 16th, they disembarked in a cove near the Wampanoag village of Patuxet, which they named Plymouth. Whether historians remember it or not, it’s an important date for us to remember as members of a church called “Plymouth,” not in a triumphal way, but in the fullness of the story. (By the way, there are 44 UCC congregations named Plymouth, 8 Mayflowers, and 51 Pilgrims.)

The story doesn’t begin in Plymouth, but rather in England around 1581 when two radical Protestant ministers, Robert Browne and Robert Harrison, concluded that the Church of England was beyond redemption, and started their own congregation in Norwich. Eventually, sensible Separatists made their way to the Netherlands, where their newfangled theology was tolerated. John Robinson, a fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and another radical minister, applied to the governors of the city of Leiden to bring 100 women and men to the city so that they could practice Reformed Christianity without persecution. In 1609 they emigrated to the Netherlands, as the first part of their pilgrimage, to what William Bradford described as a “fair and beautiful city.”

Sunday worship among the emigres consisted of extemporaneous prayers by Robinson and [their deacon, William] Brewster, the reading of several passages of scripture, psalm singing, a “preached” rather than a “read” sermon, the Lord’s Supper, and a collection for the minister’s salary and for the poor.” [1] There was no set liturgical practice, no reading from the Book of Common Prayer, as in the Church of England. And importantly, there was Christian liberty within the congregation to practice the faith as they felt called to do…not so much as an individual desire as a matter of communal practice of what they felt was authentic faith and worship. That desire was so strong that the Leiden Pilgrims left homes, professions, farms, family, and everything they knew in England.

They felt called in a way you and I can probably only imagine. They sensed that God was calling them, like God had called Abram, to go to a new land. We in the UCC really appreciate the phrase, “God is still speaking,” which was coined about 20 years ago. And those early Separatists definitely felt as though God was speaking to them with such clarity that they would risk their lives to follow God’s voice.

Things in the Netherlands grew a bit tiresome for the Pilgrim community, even as other Separatists from England joined them. Some did not want their children to integrate into Dutch society or to lose their English culture. So they prepared for a voyage to North America. Most of the congregation remained in Leiden, along with their pastor, John Robinson. On the day of their departure, they had a “day of solemn humiliation” that consisted of fasting, preaching, and feasting. Robinson warned those setting out against doctrinaire following of either Luther or Calvin, declaring, “the Lord had more truth and light yet to break forth out of his holy Word.” There it is again…a sense of progressive revelation, that God was still speaking to us. Around July 22, their ship, The Speedwell, set off for Southampton to join with other English Separatists who would join them on a second ship, The Mayflower, for the Atlantic crossing. When the Speedwell began to take on water, they put in at Plymouth, where the Speedwell’s master declared the vessel unseaworthy, and on September 6, the Mayflower set out with only some of the Pilgrims, as well as some adventurers (as investors were called) to make the crossing alone.

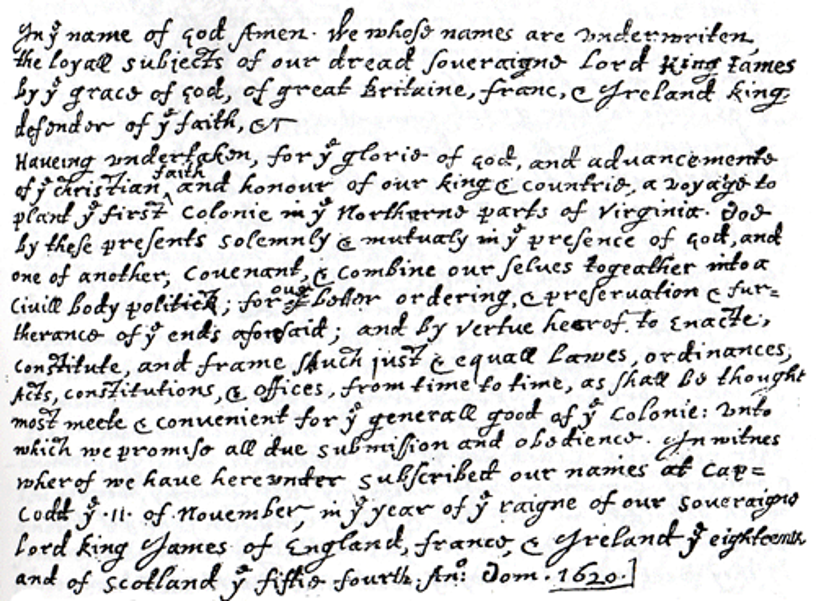

Two factors distinguished this band from the English colonists who settled in Jamestown 11 years earlier. First, roughly a quarter of the Mayflower Pilgrims were women and girls. That made it clear that they were not emigrating for a temporary stay, but to forge a new settlement. Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in the 1830s, “The civilization of New England was like a bonfire on a hilltop, which, having spread its warmth to its immediate vicinity, tinges even the distant horizon with its glow….The founding of New England presented a novel spectacle; everything about it was singular and original. The first inhabitants of most other colonies were men with neither education nor means, men driven from the land of their birth by poverty or misconduct; or else they were greedy speculators or industrial entrepreneurs…The immigrants who settled on the shores of new England all belonged to the well-to-do classes of the mother country [except for one of my mother’s ancestors who came as a servant and turned out to be a ne’er-do-well]…Here was a society with neither great lords or commoners, indeed one might almost say they were neither rich nor poor….What distinguished them most of all from other colonizers was the very purpose of their enterprise.” [2] …which was their faith and the ideal of founding a settlement grounded in their Separatist theology. It was also their political ideology, expressed in the Mayflower Compact, written shipboard while they were at anchor in the Bay and signed by all the males – Pilgrims, adventurers, and servants – but not by the women.

“We, whose names follow, who, for the glory of God, the development of the Christian faith, and the honor of our fatherland have undertaken to establish the first colony on these remote shores, we agree in the present document, by mutual and solemn consent, and before God, to form ourselves into a body of political society, for the purpose of governing ourselves and working toward the accomplishment of these designs; and in virtue of this contract, we agree to promulgate laws, act, and ordinances.” There, my friends, you have the basis of congregational polity, the way we still govern our churches, and perhaps a precursor to American democracy.

When the Pilgrims arrived in Patuxet, they found a desolated Wampanoag village and even a few human skeletons. It turns out that the English and French had been traveling the New England coast for decades, fishing and trading with local tribes. The English also took captives, and Thomas Hunt kidnapped around 20 Wampanoags at Patuxet, including one man named Tisquantum, who escaped and eventually found his way back to Patuxet, only to find its inhabitants had been wiped out by exposure to an uncertain disease, perhaps smallpox or typhoid fever, to which native peoples had no immunity. As the bitter winter was ending, Samoset, an Abenaki man, entered the village and shockingly spoke to the new arrivals in English, which he had learned from trading with the English in present-day Maine. The next day, he brought Tisquantum, whom they called Squanto, and they were led to a brook to meet Ousamequin, whom they called by his title, Massasoit, the sachem of the Pokanoket band. They quickly formed an alliance with Massasoit, agreeing that the Plymouth settlers and Massasoit’s warriors would defend one another in an attack. This was a real concern given that Massasoit’s enemies, the Naragansett people, were virtually unscathed by the pandemic that had taken so many Wampanoag lives. When Massasoit was captured by the Naragansetts, the settlers did indeed go after him, though he escaped before their intervention. In the fall of 1621, having lost nearly half the English population in their first winter and having a good harvest thanks to their indigenous neighbors, Governor Bradford decided the settlers “might after a more special manner rejoice together” and sent out parties to shoot fowl and also to fish. The Wampanoags killed five deer for the feast, and Massasoit brought 90 people to the celebration. A new history of the Plymouth Pilgrims records that “The Plymouth settlers and the Wampanoags did not always enjoy each other’s company, but on this occasion they did. ‘We entertain them familiarly in our houses,’ [Edward] Winslow wrote, ‘and they are friendly in bestowing venison on us.’ Such moments are reminders that conflict between Europeans and Natives was not inevitable.” [3] Yet within two years, the impulsive soldier-adventurer, Miles Standish, had slain a Massachusett warrior, though relations with the Wampanoags continued to flourish for a time. Part of the issue was that the Pilgrims saw themselves as being like Abram, being called into a new land, and though Patuxet was uninhabited when they arrived, there was a population of New England, just as the land of Canaan was populated. I never thought much about a town near where I grew up – New Canaan, Connecticut – but now it makes sense to me. The English cast themselves as the descendants of Abraham and the native tribes of New England they saw as the Canaanites. To me, this was a tragic misreading of Genesis and the cycle of Abraham stories. We see them as mythic retellings of a distant past and not as historical guidelines to follow. I’m glad to say that we’ve made a lot of progress in biblical scholarship over the last 400 years. And yet, today we still live with the tragic consequences of both conflicts…between Jews and Palestinians in the Middle East and in this nation, where we live and worship on land that belonged to the Cheyenne and Arapahoe people. If God does, indeed, have more light to shed, may we as the inheritors of the Pilgrim heritage have the wisdom, the courage, and the sense of justice to listen. And may we have the faith not only to confess the part our denominational ancestors played in the demise of indigenous peoples, but the courage to be advocates when we hear of oppression. Amen.

© 2020 Hal Chorpenning, all rights reserved. Please contact hal@plymouthucc.org for permission to reprint, which will typically be granted for non-profit uses.

Notes

1. John G. Turner, They Knew They Were Pilgrims. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020) p. 33. 2. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, translated by Arthur Goldhammer. (NY: Library of America, 2004), pp.36-7. 3. John G. Turner, They Knew They Were Pilgrims. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), p. 81. AuthorThe Rev. Hal Chorpenning has been Plymouth's senior minister since 2002. Before that, he was associate conference minister with the Connecticut Conference of the UCC. A grant from the Lilly Endowment enabled him to study Celtic Christianity in the UK and Ireland. Prior to ordained ministry, Hal had a business in corporate communications. Read more about Hal.

Rev. Jane Anne preaches on Psalm 149 for Hymn Sing Sunday.

“Singing for Dear Life”

Psalm 149 November 15, 2020 Plymouth Congregational Church, UCC The Rev. Jane Anne Ferguson Psalm 149 Praise the LORD! Sing to the LORD a new song; sing God's praise in the assembly of the faithful! 2Let Israel celebrate its maker; l et Zion's children rejoice in their the [Holy ONE, their ruler]! 3Let them praise God's name with dance; let them sing [the Holy One's] praise with the drum and lyre! 4Because the Holy One is pleased with people of God, God will beautify the poor with saving help. 5Let the faithful celebrate with glory; let them shout for joy on their beds. 6Let the high praises of God be in their mouths and a double-edged sword in their hands, 7t[for]revenge against the nations and punishment on the peoples, 8binding their rulers in chains and their officials in iron shackles, 9achieving the justice written against them. That will be an honor for all God’s faithful people Praise the LORD! [1] For the Word of God in scripture, for the Word of God among us, for the Word of God with us, Thanks be to God! It seems that many, many years ago, during the time of the great Rabbi Shneyer Zalmon, that there was an old man who longed to study Torah. He had been orphaned as a child and was not able to complete his Hebrew school. As a young man he married and had a family, so all his time was taken with working to provide for his loved ones. Now his children were grown and had families of their own. It was just him and his wife and there was time….time to study. So, after searching for just the right teacher, listening to many scholars, he began to attend Sabbath school with Reb Zalmon. On his first day he was so excited. He listened so intently, but as the lessons went on he grew more and more frustrated. His brows knit together. Big tears came to his eyes and even began to drip down his furrowed cheeks. As the lesson came to a close, he hung his head, shaking it sadly. The Rebbe had noticed this new one, this stranger, among the other students. He noticed his frustration and sadness. So Reb Zalmon called the man into his study after the lesson was over. “Tell me your story,” said the Rebbe, kindly. And the old man poured out his longing to study the Torah, the obstacles he had encountered all his life, and his search for the right teacher to help him. “Many scholars have laughed at me for my inability to understand…but I heard that you befriend all men…so I chose you to be my teacher. I listened with joy today as you explained the Torah, yet I found that I still could not understand what you were saying. And my heart is broken. All my life I have been sustained by reciting the Psalms…but I long to understand the Torah. Tell me, what must I do to understand, Rebbe!” Tears were now streaming down the man’s face. Reb Zalmon put his hand on the man’s shoulder and said, “No more tears, my friend. It is the Sabbath and on the Sabbath we rejoice.” The Rebbe continued, “What you heard today were the teachings on the Torah from the great Rabbi, may his name be preserved forever, the Baal Shem Tov. Since the words have not hit home for you, I will sing you a song that contains Baal Shem Tov’s thoughts.” And Reb Zalmon sang a sweet melody with beautiful lyrics and the man listened like a pillar of attention. He didn’t move an eyebrow. When the song was complete, his face was glowing with joy. “My soul has been transported. I understand, Rebbe! And now I feel worthy to be your student.” And from then on Reb Zalmon always sang that melody at the end of his teachings as a way of clarifying the thoughts he had just shared on the Torah. And that’s the story of “The Rebbe’s Melody.” As a preacher and one of your pastors, I wish I had a special song to sing at the end of each sermon to clarify all I have just said. But really isn’t that what hymn singing in our services can do if we listen carefully…. to the melodies as well as the words. Some of us don’t think of ourselves as singers…yet we can all be listeners and ponderers of lyrics. I venture to say that of some form or fashion music moves us all. Music teaches us in ways that mere words cannot…because it engages our bodies with movement and engages our emotions. It moves us from our heads to our hearts. Each week we, as a worship team, carefully choose the music to illumine the scriptures that we hear and the teachings in sermons. And I believe the hymns and songs and all the worship music stand along as mini-sermons/meditations on the word from scripture. This week we heard Psalm 149, a psalm of praise to God, the Creator, the ultimate leader of all God’s people in the faithful assembly. In my progressive Christian theology that means to me ALL the people of the world, no matter their religious practice or lack thereof. And in this psalm we are reminded that because of all the faithful and beloved people of God, the poor and oppressed are “beautified”….therefore the faithful are given a “double-edged sword” to vindicate God’s ways of justice and peace and abundance, to defeat the nations and rulers whose ways are oppression and injustice. The war language is startling to us and is unusual for a psalm of praise. But I dare to read it this morning – even as I acknowledge the devastation of too many human holy wars down through the century – to remind us of the serious connection of singing and working for God’s realm of justice on this earth revealed to us in the Hebrew scriptures and in Jesus the Christ. We do not take literal weapons to work for God, instead we are called to acts of justice and non-violent resistance, kindness and sharing that are counter-cultural, counter-intuitive to the warring ways of humanity. And we are called to this understanding of our calling as people in the faithful assembly of the Holy One by a psalm, a song, a hymn! What might the hymns we love, the hymns we sing – those familiar to us and those unfamiliar to us – be calling us to each week? How is God speaking to us, what is God speaking to us in our hymns? Comfort, yes….and also challenge! When we sing in worship we are singing for dear life! The dear life of God’s realm here and now among us and coming into being. I invite you as a preacher…if the scripture and the sermon do not make sense to you….look to the hymns! Reb Zalmon knew about the mystery of God in scripture and the call of justice for all people when he sang to the old man. He knew it was an act of justice to illuminate God’ word for every person, so all may understand the love of God, when he sang: All the angels, all the seraphim Ask who God, [the Holy One], may be. Ah woe, what can we reply? “No thought can be attached to [God] All the people ––– every nation ––– Ask where God, [the Holy One] may be. Ah woe, what can we reply? “No place is without God.” [2] May it be so. Amen. [1] Bible, Common English. CEB Common English Bible with Apocrypha - eBook [ePub] (Kindle Locations 24148-24157). Common English Bible. Kindle Edition. [2] Yiddish Folktales, Beatrice Silverman Weinreich, ed., Leonard Wolf, trans.(New York, NY; Schocken Books, Inc., YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 1988, 272.) Pastoral Prayer Holy One, sing to us like a mother lullabies of peace and comfort in our troubled times of pandemic, conflict and division. Sing to us your song of challenge and courage that we may stand against injustice and hatred with your fierce love. As we pray this morning with the words of our mouth, with the longings of our hearts and the music of our souls, we join you in lament for lives of loved ones lost, for the millions of beloved lives lost to the Covid 19 virus. We lift prayers imploring you to stand with us as seek to keep all safe from this illness, to heal all who are struggling with it, to protect those on the frontlines of essential workers who risk their own health and safety to serve other. We lift our prayers of lament for lives lost to the violence of racial injustice. Turn our hearts, Holy One, toward your realm of courageous love that is already here with us on earth. Open our eyes to see the joy of your love in Christ Jesus that is always present in beloved community, in the beauty of creation, in the eyes of your people. All this we pray with the word of love Jesus taught us to use… Our Father (and Mother) who art in heaven…. ©The Rev. Jane Anne Ferguson, 2020 and beyond. May be reprinted with permission only. AuthorAssociate Minister Jane Anne Ferguson is a writer, storyteller, and contributor to Feasting on the Word, a popular biblical commentary. Learn more about Jane Anne here.

Rev. Carla preaches on the wise and foolish bridesmaids.

AuthorRev. Carla Cain began her ministry at Plymouth as a Designated Term Associate Minister (two years) in December 2019. Learn more about Carla here.

Romans 12.9–18

The Rev. Hal Chorpenning, Plymouth Congregational UCC Fort Collins, Colorado The family I grew up in was very antiseptic about death. They didn’t like funerals…they preferred memorial services after the fact. They didn’t talk about death, and I’m not sure they really knew how to grieve and mourn. I knew something about that was not healthy, especially after my dad died when I was 25. About ten years later, I was a Stephen Minister at First Congregational UCC in Boulder and a first-year student at Iliff. I was paired with Roy Brammell, a delightful, wise man in his 90s who had been the founding dean of the School of Education at the University of Connecticut fifty years earlier. And when I joined the family to visit Roy’s body at the mortuary, as I saw his tall, thin body, and it struck me that this was an empty shell…that Roy was no longer there. To me, it seemed that the body and the spirit were no longer connected. The senior minister, Bruce MacKenzie, asked if I’d like to help lead Roy’s service, and I said I’d be glad to. For the service, Roy’s adult children collected some of the things he had written over the years on a wide variety of topics like citizenship, education, duty, faith, and so on. They took turns reading these heartfelt pieces Roy had written, and it seemed to bring Roy’s presence back, even to revivify his spirit. (And I started crying in the chancel, and I had no Kleenex…so that was a lesson learned…never lead a memorial service without Kleenex.) Roy’s community of faith gathered to offer thanks to God for his life, to send him off prayerfully, to remember him, to surround is family in a loving embrace, to “rejoice with those who rejoice and to weep with those who weep.” Everybody has a story, whether we are homemakers or professors or deans or clergy or laborers or physicians or farmers or unemployed or businesspeople. God knows our stories…and I think it is a natural sentiment that we want others to know our story, and I suspect that we all want to be remembered. That’s an important function of a funeral or memorial service, or even of the bronze plaques honoring those buried in our memorial garden at Plymouth. Sometimes when I go by those names at the end of our gallery, I touch the bronze plaques, intentionally recalling the people named there, and I remember their stories and pray for them. I have a strange affection for old cemeteries, especially those attached to Congregational churches in New England. Looking at the artwork and reading what people chose to record on gravestones makes me curious about the stories of the people they commemorate. One of my favorite cemeteries is at First Congregational Church in Kittery Point, Maine, where I served as the sabbatical interim minister during the summer when I was in seminary. It’s a beautiful location on the shore, overlooking the harbor where the Piscataqua River flows past Portsmouth, New Hampshire into the Atlantic Ocean. I did some gravestone rubbings when I was there, and one struck me particularly, and I have a rubbing of it hanging in my office. It is the headstone of The Rev. Benjamin Stevens, who lived from 1721 to 1792. Stevens had to walk a fine line during the American Revolution between Tories and Patriots, and in 1776, the wealthiest family in the church, the Pepperells, left Maine for England, never to return. (The church still uses the communion silver and baptismal bowl given by their patriarch Sir William Pepperrell.) Everyone has a story, and here is what we know of Benjamin Stevens from his gravestone: “In memory of the Rev’d Benjamin Stevens D D Pastor of the First Church in Kittery, who departed this life in the joyful hope of a better, May ye 18th 1791: in the 71st year of his age and 41st of his ministry. In him, the Gentleman, the Scholar, the grave divine, the chearful Christian, the affectionate, charitable & laborious Pastor, the faithful friend & the tender Parent were happily united.” With that eulogy in stone, Stevens’ story inspires me as a pastor 229 years later. When Stevens died, a minister from nearby Portsmouth preached at his funeral, and accounts say that Kittery harbor was filled with boats from near and far, and that the crowd overflowed from the meetinghouse. This is one of the things that churches do: we help to remember the people whom we have loved and who have died. We help to provide a ritual that helps those in grief to have a place to mourn with others, to receive love and support from friends and fellow parishioners, and to be the church for one another. And there is more…we offer prayers for those who have died. We commend their spirits into the arms of God, asking for them to be received “into the company of the saints of light.” Maybe if you’re young or if you’ve never had a brush with death, it may not seem terribly important to you, but when I die, I want someone to pray for me. A funeral or memorial service is more than a celebration of life, it’s also an act of giving thanks to God, who entrusted the gift of life to us. As a church, we gather on this Sunday every year to name those dear ones who have died since last year at this time. It is a poignant and deeply meaningful rite that we observe. Year after year, we come together to name the names, to recall the people and their stories, to lift them up to God in a spirit of love and remembrance. This is another reason it’s almost impossible to be a Christian without a community around you. Even when we have to wear masks…even when we’ve used more hand gel than we could have imagined using in a lifetime…even when we are worshiping together via Vimeo, even when we can’t give one another a physical hug…we are here for one another not only for ourselves, but as the hands and feet, eyes and ears of Christ in the world today. “Let love be genuine; … hold fast to what is good; love one another with mutual affection…Rejoice in hope, be patient in suffering, persevere in prayer…extend hospitality to strangers….Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep. Live in harmony with one another…and live peaceably with all.” Paul gives us a tall order, but I know that this congregation — even in the midst of a pandemic, even on the cusp of a divisive election — this congregation will be there for one another and for our community. I’ve seen you hold the light for one another when someone is experiencing the shadows of grief and despair. God calls us to be there for each other, and you do that with grace, openness, and generosity of spirit. So, let us enter a time of remembrance for the people we’ve loved and lost these past twelve months. Let us remember their stories, and let us hold one another in our hearts. © 2020 Hal Chorpenning, all rights reserved. Please contact hal@plymouthucc.org for permission to reprint, which will typically be granted for non-profit uses. AuthorThe Rev. Hal Chorpenning has been Plymouth's senior minister since 2002. Before that, he was associate conference minister with the Connecticut Conference of the UCC. A grant from the Lilly Endowment enabled him to study Celtic Christianity in the UK and Ireland. Prior to ordained ministry, Hal had a business in corporate communications. Read more about Hal. |

Details

|